Arch SA

One Of The Unknown Other

The debate on defining a South African architectural identity is not inconclusive: it is problematic − like all debates around every protest in the news over the past few years; like the Oscars blunder was a hot topic the other day.

The issue of identity is at the debate’s core. That one has no identity to begin with is the problem. When there’s a protest against one history subsuming that of another, it’ a storm in a teacup. When it passes, it’s anecdotal.

The Fees Must Fall movement wasn’t merely about the affordability of education. It was an imperative bell ringing for us to sit up and look at how we teach and learn, what we learn, why we learn and what that learning will produce. Decolonising − education, architecture − is not about unlearning, but interrogating what was and is taught. We must acknowledge that there are alternative perspectives to feed architectural discourse in all its manifestations.

That interrogation should uncover the complexities of our diverse demographic makeup – black, white, coloured, Indian… other. It is about finding and employing the alternate learning; learnings connected to my identity as a coloured woman; learnings that create meaning for me and make it easier for me to say to my nephews: this is your culture.

Tunde Oluwa’s article (ArchSA 83) referred to the education of the young black architect, while Professor Gerald Steyn’s (ArchSA 84) proposed engaging black architects in a debate about ourselves. I found both poignant and incensing because little has changed since I was a first-year over 25 years ago. Black students still face issues of confidence, resources, relatability and ability, like I did. Questions of competency (even by other black clients/consultants) are still part of the practice landscape. The closed debate around Afrocentricism – a contentious term − in architecture is still mostly held in academia. It is still problematic that the definition is reduced to a stylistic discussion.

Having had the privilege of teaching at two universities over the past six years, it is evident that curricula are slowly changing. Lecturers are more cognisant of their transformational mandates. Better- informed teachers mean students get a more relevant education, with some exposure to issues they’ll deal with in practice. But this is happening in small pockets, probably not in every architecture school. Are students entering practice equipped to deal with this debate?

At some point, we will have to become impolite about race and gender in the architecture and built environment discourse. We will have to teach and learn black architectural academic history − there were actually black women architects, such as Norma Merrick Sklarek, making buildings before we were all conscientised.

We have to be more aware that (black) bodies occupying space creates a language of architecture that is about more than form. It is psychosocial, economic, political. And we are so afraid of politics. Yet we are so privileged to have our politics, and our space- and city-making agendas, so closely knit − at least in the same building, if not the same room. This should encourage us to scrutinise them closely.

The architecture of transformation does not merely ask for relevance. It asks for redressing. It asks uncomfortable questions about ownership and space. How do you make an inclusive city/built environment when it is spatially, historically, economically and aspirationally divided and contested? Perhaps one could start by not perpetuating apartheid-style thinking about, for example, how you renovate single dwelling units for male occupants into family living spaces.

The architecture of transformation asks whether the people making and thinking about space are the right ones for the job. Are we? How do you create economically and spatially viable urban platforms when the diverse communities inhabiting the urban fabric have no cohesion, have their identities and space-making practices erased and challenged by policy and political grandstanding? How do you ask practising architects to forget what they’ve been taught and rethink why they are architects?

I don’t have any answers.

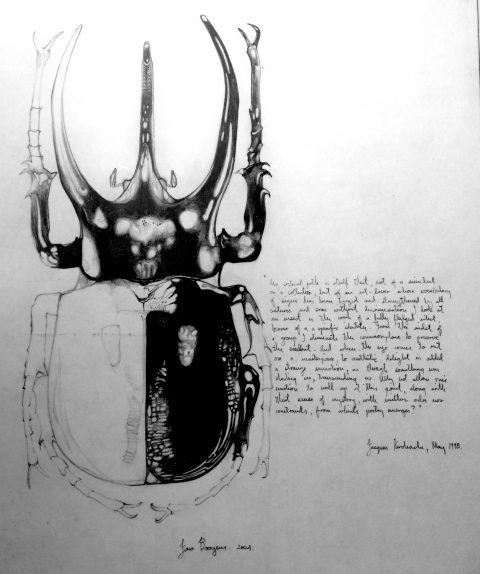

As one of the unknown of the 21% of registered black woman architects referred to in Professor Steyn’s article, I want to fool myself into thinking that hard work and dedication are sufficient. That it matters little that I am a black female architect. That my particular perspective is valued, and that I don’t have to confront the monster under the bed − my coloured identity, codified and defined by others.

But the monster under the bed has woken and is asking questions.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.