CSI

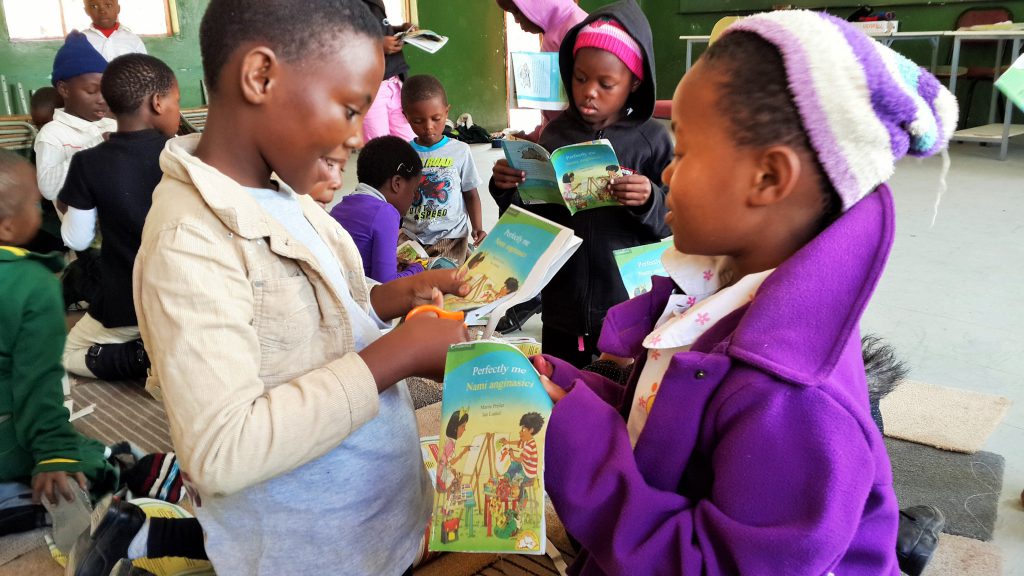

A Holistic Approach To Literacy

Despite South Africa having one of the highest rates of public investment in education in the world, about 60% of the country’s children cannot read at basic level by the end of Grade 4, according to research by the Department of Economics at Stellenbosch University.

Research from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee shows that parental involvement in children’s literacy development at an early age is very important for school success. But, according to the Minister of Basic Education, Angie Motshekga, only 14% of South Africans read books, so children are missing out on this crucial intervention within their homes.

Family literacy is a term used to describe parents and children – or more broadly, adults and children – learning together. Most literacy projects in South Africa tend to focus on children, so the Family Literacy Project (FLP) is unique in that it encompasses the entire family. This nonprofit organisation operates from a training and resource centre in the small town of Underberg on the foothills of the Drakensberg in KwaZulu-Natal.

Its slogan is Masifunde Njengomnendi (Families Reading Together) and its main aim is, “To make literacy a shared pleasure and a valuable skill”

FLP operates in communities in Underberg and neighbouring Himeville, as well as in surrounding rural communities.

Here, nearly 10% of adults aged 20 years and older have no schooling, and a further 23.88% have not completed primary school. The municipality of Ingwe in the district has an unemployment rate of 39.3% and a youth unemployment rate of 48.5%, while unemployment rates in Umzimkhulu municipality are in excess of 40%.

According to Pierre Horn, FLP’s director, the programme differs from state adult education and training centres. “We focus holistically on family literacy in ways that include children, parents and caregivers, and which respond to the needs and concerns of participants, drawing upon their assets and resources,” he explains. “FLP does not offer formal adult education qualifications such as the General Education and Training Certificate and the National Senior Certificate.”

Horn says that they see the entire family rather than the individual learner as the key to literacy development within a community context. “We understand that developing the literacy skills of adult caregivers has a positive effect on their children’s literacy,” he says, “and that developing the literacy of women as a group influences the literacy and development of the wider community in which they are situated.”

Funding hard to come by

Horn admits that funding is a pressing issue for them, especially with donors and investors constantly changing priorities and budgets.

According to Trialogue, a consultancy that focuses exclusively on corporate responsibility issues in South Africa, education is the highest recipient of corporate social investment (CSI) expenditure in South Africa, with 92% of companies reported supporting education projects in 2014.

In 2014, nearly half (49%) of all social investment expenditure went towards supporting education, up from 38% five years prior. More than a third (35%) of this expenditure went to maths and science initiatives, 19% went toward Early Childhood Development (ECD), and only 3% of the funding went toward adult education.

Family literacy, while falling under the gamut of education, doesn’t receive as much support as areas such as ECD and general and tertiary education. Horn explains that FLP has managed to source corporate support from various companies and individuals. These include the DG Murray Trust, which distributes about R110-million in grants to public-benefit organisations each year.

The DG Murray Trust has funded FLP’s Community Work Programme (CWP) for several years. Participants are trained to conduct literacy home visits in the districts of Sisonke and Impendle and bring learning right into the home. Other corporate benefactors include Mondi International, a packaging and paper group with a paper mill in Durban and a pulp and liner-board mill in Richards Bay, as well as the National Lottery, and the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Arts and Culture.

In South Africa, big contributors to education include Barloworld, which gave R15-million in 2014/15. Most of this went toward ECD programmes and improving maths, science and languages. The Telkom Foundation is another big backer and invests R3-million annually into its Rally to Read initiative, which supports Grade R-7 literacy in rural and disadvantaged schools. Nedbank’s Spell It focuses on literacy through vocabulary building in Grade 4, and spelling bees at Grade 5 and 6 level.

Since the need is so deep and resources scarce, FLP has figured out a way to generate some funds by working with government programmes such as the CWP in local municipalities.

Among FLP’s challenges is the scarcity of learning resources, especially appropriate reading materials in isiZulu, which they have tried to remedy by developing and sharing their materials.

Horn states that while corporate support is welcome, the best results are achieved when there is a long-term partnership where the investor stays abreast of what is happening on the ground, and can make informed decisions when supporting them. FLP’s financial and administrative systems are based on a shared vision and the values of accountability, honesty and carefulness with resources.

FLP’s approach emphasises the notion that parents are the “first teachers” of children and their influence is crucial to children’s later progress at school. Although the methodology differs from typical public adult education centres in that learners do not write exams or study for formal qualifications, it addresses the needs of rural learners, especially women, by focusing on their concerns and contexts.

The organisation draws deeply on the assets and resources of these communities, for example, using facilitators from the communities so that the community has ownership of the project and feels comfortable with who is leading it.

A 2006 evaluation found that after home visits by facilitators, children were able to recognise pictures, respond when asked questions, enjoy reading, and keep books safe and clean. Parents learnt health and nutrition messages such as the importance of breast-feeding, washing of hands, treatment of diarrhoea and immunisation.