CSI Sunday Times

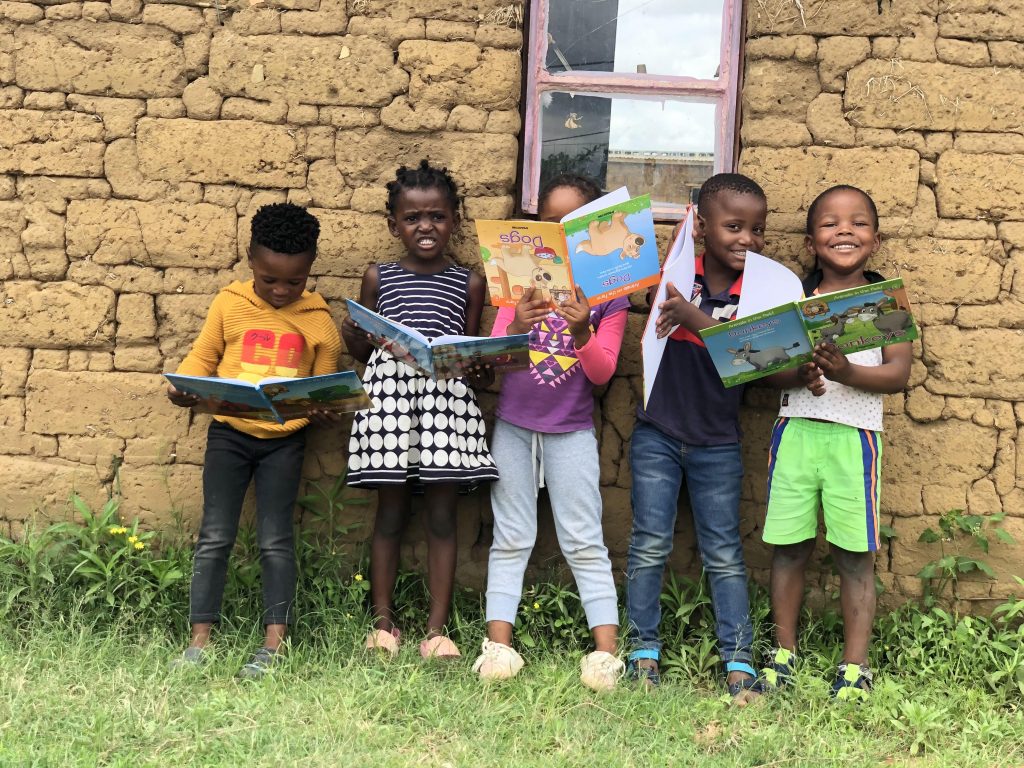

Quality Early Life Development

The Department of Basic Education has taken on the herculean task of providing all South African children with access to quality early childhood education programmes by 2030. That is less than eight years away, and there are currently upwards of 1.2 million children who start school each year unprepared for primary school, notes Candice Potgieter, CEO of The Unlimited Child.

Partnerships for success

Organisations involved in improving access to early education agree that partnerships with government, civil society, corporates and the beneficiaries of early childhood development (ECD) programmes are critical if South Africa is to turn the tide. “With the high volume of children younger than six unable to access good early learning, it is essential that civil society partners with the government to realise the common goal of creating effective learning systems and environments for children to thrive,” says Potgieter.

The Santa Shoebox Legacy has a two-tier partnership approach, with the first tier being donors from the corporate and private sectors. The second tier is the beneficiary partners themselves. “Upskilling key players in small communities will create a long-lasting difference, so we endeavour to find beneficiary partners who are willing to participate in the long-term success of the project,” says Samantha Massey, project manager at the Santa Shoebox (SSB) Legacy.

Celebrate early learning

Nomvula Matlare, brand marketing and communications lead at SmartStart, a nonprofit organisation that focuses on improving access to early learning for children aged three to five, calls for a renewed interest in early childhood learning in general. “We need this country to be as obsessed with the progression of children from early learning to primary school as it is when children complete their matric.” Without a solid foundation, a child starting school may lack the confidence and ability to succeed and ultimately complete high school. Potgieter agrees, saying: “Research has shown that unless children aged 0–6 are exposed to learning through play, which includes concepts that teach early numeracy and early literacy, their potential in life is severely limited.”

The push to make early learning widely accessible is not just setting up children for a successful school career, says Grace Matlhape, CEO of SmartStart. It also ensures that we have future generations of adults able to contribute to the country’s economy. In the medium-term, it makes it possible for parents to concentrate on their work or careers while their children are being educated, so that parents can realise their full potential and support their families.

Poor infrastructure

An ECD centre must meet certain criteria to be registered with the Department of Basic Education and receive government funding. However, many ECD centres do not have the infrastructure or means to comply. Without funding, many centres cannot jump through the hoops required to register, says Massey.

The health department also needs to provide a certificate of compliance, and with many ECD centres operating from containers, back rooms, or empty church halls, it can sometimes take years for a facility to tick all the boxes and be registered, she says. Meanwhile, the centre must operate without funding. It’s an unfortunate cycle that forces many ECDs to operate without being compliant.

Lack of funding

Santa Shoebox Legacy uses funds from corporate and private donors to transform ECD centres in rural and underprivileged communities, says Massey. This financial support is used to address societal issues such as the need for educational funding, the demand for training among educators, access to potable water, increasing the literacy rate and early childhood nutrition for growth. “Uplifting communities holistically and sustainably assists the government in the massive tasks of addressing the very poor standards of childhood education currently being experienced in rural and underprivileged communities.”

Teachers need ongoing training to give the children in their care the best education, she adds. Many often receive no fees or, at best, a nominal stipend. “This is another area where it is vital that we as the SSB Legacy Fund partner with NGOs that are capable of offering this to teachers.”

Adequate training and resources

Rays of Hope, a nonprofit company working with numerous NGOs, schools and ECD centres in Alexandra in Gauteng, provides support by helping with additional training for teachers, ensuring adequate classroom resources and sharing best practices with local ECDs. “The ECDs in vulnerable communities are literally daycare centres where they look after learners until the parents or siblings come to pick up the child from the centre,” says Bafana Mohale, education programme manager at Rays of Hope.

He says many of the centres do not have a set curriculum or teaching plan, and few of the teachers are qualified ECD practitioners. “These challenges are why our children in public township schools typically lag their counterparts in better-resourced schools: South Africa’s learners are classified as having among the worst literacy and numeracy levels in the world.”

SmartStart addresses the dearth of adequate training by using a social franchise model to tap into the experience of existing civil society organisations that recruit, train and license women to run their own early learning social enterprises. Part of the programme is the provision of a daily routine and SmartStart PlayKit, which promotes free play in a language-rich environment and encourages interactive storytelling and the development of self-regulation.

SmartStart has an established network of over 90 000 parents and caregivers whose children are enrolled in its programmes.

The model also works with parents to help them understand that their children need to attend early learning regularly to benefit. “Parents need to be involved as well,” she says.

Creating opportunities

While there is a definite need for early learning in vulnerable communities, there is also a demand from micro entrepreneurs who want to formalise the work they do in the ECD space, notes Matlhape. SmartStart has almost 6 000 franchisees who “need a sense of agency and worth”. Together, they form a powerful network of ECD centres where creating a nurturing and safe environment for children is paramount.

ECD centres have burgeoned in vulnerable communities in response to the need for early learning. As franchisees, these practitioners are screened and given proper training and resources. The reality of where many of these centres are based cannot be overlooked. When one is teaching children in a container or a shack, it can be challenging to meet the requirements for health and safety.

The Unlimited Child creates opportunities by working with government and the community to unlock opportunities for pre-existing ECD centres to become viable micro enterprises. By partnering with infrastructural and nutrition partners, the organisation can ensure the ECD environment is primed for the delivery of effective learning through a play environment, explains Potgieter. Furthermore, the Unlimited Child works with the government to ensure that data sets, analyses, and on-the-ground assessments of ECD centres are easily communicated. This means that best practices can be quickly duplicated, she adds.

Through partnerships, ECD centres can provide additional services to ensure the wellbeing of the child and their families. Potgieter explains that, during the height of the pandemic and recently with the floods in KwaZulu-Natal, The Unlimited Child was able to mobilise collective resources to ensure that families could be sustained through the ECD centres their children attend. Most of The Unlimited Child’s 3 050 ECD centres throughout the country have remained open despite the challenges of the past two years.

Most of the organisations involved in ECD programmes have welcomed the decision to shift responsibility for early learning to the Department of Basic Education. But the only way to ensure that children who are currently in the system at ECD centres that may not have safe toilets or a safe outdoor play area, and may not comply with the requirements to be registered, also benefit is by forming partnerships. “By finding the right partners, we can chip away at this seemingly insurmountable mountain and make a huge difference, even if it is only one school at a time,” concludes Massey.