SA Mining

Fired Up

Firestone Diamonds’ Liqhobong Mine, a new kid on the block in terms of diamond production, is looking to reap the rewards of a rough diamond demand projection of between 1% and 4% per year. This is forecasted by global management consultancy firm Bain & Company’s report The Global Diamond Industry 2017: The Enduring Story in a Changing World, recently appointed CEO Paul Bosma tells SA Mining.

The AIM-listed rough diamond producer holds a 75% interest in the Liqhobong Mine in Lesotho with the government of Lesotho holding the remaining 25% on its flagship project, which delivered beyond expectations in its first full year of production in July.

According to Bosma, although the rough diamond market is currently under pressure, for smaller lower-quality goods the long-term fundamentals for the natural diamond market remain strong given the limited supply of fundamentals predicted for the medium to long term.

“Demand for diamonds from the US market is expected to remain strong while the Chinese and Indian markets are scheduled to post continued growth going forward – this is on the back of a growing middle class,” he said.

The US remains the largest consumer of diamonds at 48% of polished production, followed by China at 16%, the Middle East at 7%, Japan and India at 5% and 6% apiece, and the rest of the world accounting for 19%.

Despite the rosy outlook forecast for the medium to long term, the market for rough diamond stones that are lower quality and less than 0.5 carats in size is facing strain.

According to Bosma, diamond producer De Beers’s decision to allow sightholders the option to defer the purchase of lower value smaller stones at its Site 7 sale, held in early September, is a case in point. “This is an indication that this particular segment of the market is currently facing difficulties.”

Key reasons for the low demand and subdued prices include:

■ An oversupply of smaller sized diamonds.

■ Liquidity issues and lower profit margins being experienced by major cutting centres in India.

■ The depreciation of the Indian rupee which negatively impacts the polished market given that it purchases rough diamonds in dollars.

■ The negative sentiment due to lab-grown diamonds (LGD) and uncertainty around the Lightbox initiative.

On a more positive note though, demand and pricing for better-quality rough goods remain steady, notes Bosma, who explains that from a polished market perspective, buyers of polished stones and retailers were “building high stock levels ahead of Thanksgiving and Christmas celebrations in the US followed by Chinese new year celebrations in February”.

According to the latest De Beers Insight Report, the global consumer demand for diamond jewellery increased by 2% in 2017 to $82-billion due to sustained robust growth in the US and a return to growth in US dollar terms in China.

Drivers for diamond products

According to Bosma, the drivers that ensure diamond demand remains in a healthy state include factors such as a robust appetite from leading nations (US and China), a successful marketing strategy associating natural diamonds with love and commitment, a continuing traditional stance taken by millennials as related to love and diamond engagement ring proposals and favourable long-term projections.

He cites De Beers’s Diamond Insight Report 2018 which highlights that the demand for diamond jewellery continues to be for diamond engagement and wedding rings, and remains strong in both the West and Far East.

Further, acceptance of the traditions associated with love and marriage continues to be upheld by millennials and acts as a driver for diamond jewellery demand.

Bridal diamond jewellery currently accounts for more than a quarter of the value of all diamond jewellery acquired by women in the US, China and Japan.

“For the diamond industry, millennials (21 to 39) are an important consumer segment (29% of the world’s population) with an average first marriage age of 24 to 30 in the main diamond-consuming countries. Gen Z, who represent the consumers of the future, are only now coming of age – they will have a growing impact on what consumer businesses need to offer and how marketers need to communicate in the near future. The cohort is bigger than the millennial generation and represents 2.6 billion or 35% of the world’s population,” says Bosma. China and India currently represent only 16% and 6% respectively of world diamond consumption and are therefore a huge potential market.

However, from a supplier perspective, the total diamond production in 2018 is expected to fall slightly from 2017 levels. This is largely owing to Russian diamond miner ALROSA’s suspension of operations at its Mir mine in Russia due to flooding and Rio Tinto’s guidance of falling production from its Argyle mine following the proposed closure of the mine in 2020.

“Production is expected to continue to fall as new projects and expansions fail to replace lost output from closing mines. By 2025, several large mines will reach the end of their life, while only a few new projects are in the pipeline.”

Are lab-grown diamonds (LGDs) a threat to natural diamonds?

“De Beers’s recent marketing and selling of LGDs under the Lightbox brand set the cat among the pigeons,” states Bosma.

“They are offering LGDs at much reduced price points and marketing it as fashion jewellery which clearly sets it apart from the premium natural product.”

Currently the LGD jewellery market constitutes only 2% of the diamond jewellery market by value – in other words, the LGD market is $1.9bn compared to the $87bn natural diamond market. Current forecasts by diamond analyst Paul Zimnisky indicate that the LGD market share will grow to a total value of around $15bn by 2035 but that will only constitute an estimated 5% of the diamond jewellery market and 7% of the fashion jewellery market.

“Given the relatively low supply, LGDs are not expected to pose a significant threat to natural diamond production,” notes Bosma. “Substitution risk however exists at the lower end but the impact remains to be seen.”

Liqhobong Diamond Mine

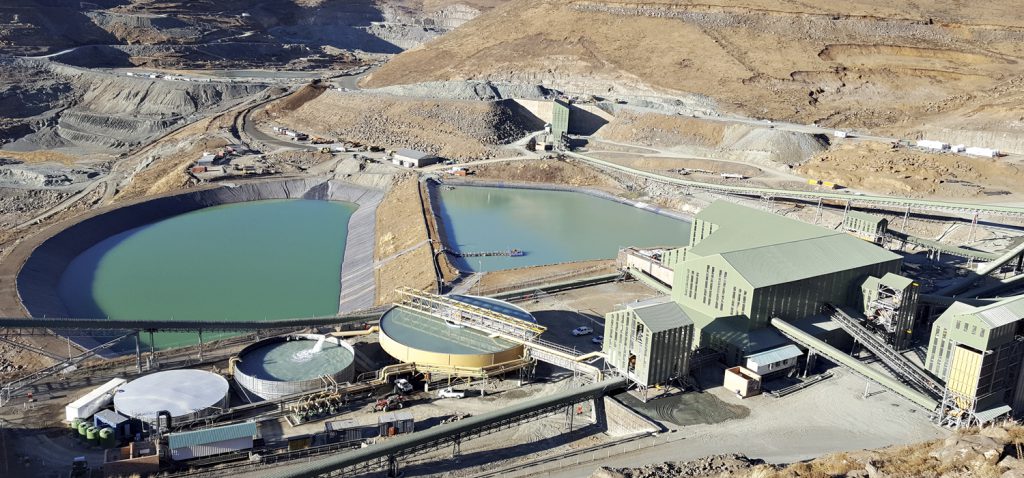

Firestone Diamonds’ flagship asset, the Liqhobong Diamond Mine, is located in the diamond-rich Lesotho Highlands – an area which is also home to Namakwa Diamonds’ Kao Diamond Mine in the Butha-Buthe district, Lucapa Diamond Company’s Mothae mine and Gem Diamonds’ Letšeng mine. According to Bosma, all four mines are located within a 100km radius of each other.

Firestone Diamonds is an AIM-listed diamond producer. It commenced production in 2016 and reported its first full year of commercial production in July this year.

The company is extremely satisfied that its new plant has exceeded nameplate production – the plant treated 3.8mt of ore for the year from which it recovered 835 832 carats of diamonds, selling 831 637 carats at an average of $75/ct.

Compared to the other mines in Lesotho, the Liqhobong mine is a high-volume higher-grade mine that recovers a variety of diamond types including its signature yellow fancy stones.

“We are using the current financial year to mine across the orebody in order to determine conclusively the average diamond value. Up to now we’ve had some promising recoveries including two stones that were +100 carats, two stones that sold for over $1-million each, and our highest value per carat stone which retailed at $112 000/carat, which was a fancy pink.”

In December last year, the diamond producer agreed a restructuring of its debt facility with Absa, and also raised $25m to shore up its balance sheet. At the same time the company revealed a revised nine-year life-of-mine plan for Liqhobong aimed at maximising cash flows.

“The short-term strategy is to use the time afforded by the debt restructuring (debt holiday until June 2019) to mine across the kimberlite fancies in the pit to determine the diamond footprint value. We currently have a nine-year LOM plan but are looking at opportunities to extend the life by steepening pit slope angles.”

This will allow the diamond producer to realise its longer-term strategy of ensuring that “we have the best possible life-of-mine plan that provides maximum value to all shareholders and stakeholders”, explained Bosma, who took over from Stuart Brown earlier this year.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.