Business Day Human Rights Day

Equitable Education Is A Human Right

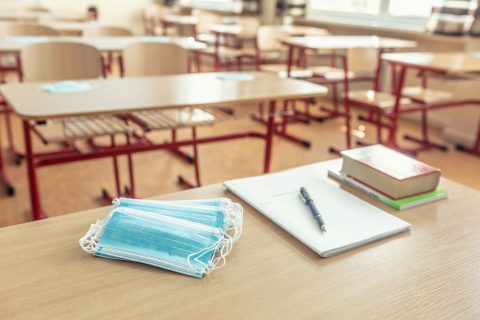

The pandemic-enforced lockdown split the South African school system into two – the schools of the privileged and the schools of the poor. Of course, the inequality was always there, but it became much more visible. For the privileged, there was a more or less seamless transition from face-to-face learning (pre-lockdown) to online learning (lockdown) to hybrid forms of learning (post-lockdown). For the children of poor and working-class communities, there was at best a WhatsApp facility to use if and when data and devices were available. At worst, these children were given printed materials that parents collected from school or teachers delivered to homes.

Equitable education is a human rights issue. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights makes clear that “Everyone has a right to education [and] education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality ….” SDG4 (Sustainability Development Goal 4) sets the following target, “all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes”.

What needs to be done?

These are aspirational goals worth clinging to even if their attainment seems so difficult in the political economy of South African education. In other words, these are goals that can and should be used to keep the feet of the powerful to the fire. It is unconscionable that life chances can be so emphatically decided early in a child’s life, dependent on the school their parents can afford. How do we change this, short of a revolution in our political and economic thinking?

One, we must ensure that every school has access to data, devices, and reliable connectivity. Without these basic resources, there is no chance of bridging the educational divide. The familiar model of teacher and textbook is a thing of the past. The sheer speed of development of “platform pedagogies” will make traditional face-to-face teaching obsolete as the sole medium for teaching and learning. The future promises more pandemics (and, therefore, disruptions to our standard model of education delivery). Even the coronavirus, say experts, will be with us in some other variant forms for a long time to come. Where previously governments built schools, they now have to build technological infrastructures capable of adapting to the new realities of 21st-century teaching.

Two, there is no way that such infrastructures can be built without a partnership between the public and private sectors. Governments do not have that kind of money, but nevertheless, carry the responsibility for public education. The private sector can make a massive contribution and do so out of self-interest; the next generation of workers will need to be fully equipped with competencies derived from technology-intensive learning. Somebody needs to say this, the National Development Plan is now obsolete; it must be urgently reconceived and rewritten with pandemic realities in mind.

Three, the training of pre- and in-service teachers must be radically overhauled to prepare them for this new reality. Universities, as institutions, are slow to change, but this reimagining of higher education in the service professions, for example, teaching and medicine, will have to adapt or fail the children served by new graduates. Attuned leadership is, therefore, needed at all levels of the education system.

My greatest fear is that the country will reset once everyone is vaccinated and that it will be business as usual. The rich will get richer, the schools of the privileged continuing to invest in the kinds of technologies that widen the digital gap. Those schools serving poor and working-class children will fall further behind as teachers scramble to find a textbook for every learner while parents struggle to keep up with school fees.

The closing of the digital gap is a soluble problem. However, it requires leaders with unquestionable ethics who are unswerving in their commitment to delivering on the technology and learning needs of all schools. If this does not happen, then we should stop talking about human rights as a political obligation in word alone.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.