Social Justice

An Unjust Education System

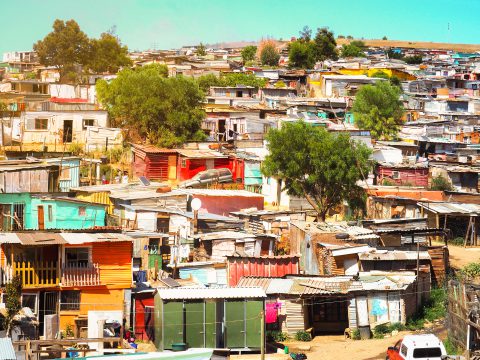

The school system in South Africa is manifestly unjust. Within a short driving distance of any major metropole, you could find a school with a state-of-the-art aquatic centre under the same education authority as a school with a pit latrine toilet where every now and again a primary school child drowns in faeces. There are endless contrasting examples of inequalities between elite public and private schools on the one hand and peri-urban and rural schools on the other.

That much is well-documented and indeed well-established in the public mind. I want to reflect on how we deal with and why we came to accept such visible injustice.

Inequality in the system unpacked

This does not mean that there are no civil society actions against educational inequalities.

The Equal Education social movement has established a reputation by making photographically visible in the public mind the atrocious state of school infrastructures, especially in rural areas of the country. It has also dragged the different ministers of education to court to enforce compliance with government norms and standards for school buildings.

Yet, despite the depiction of South Africa as a “protest nation,” uprisings are often about other things rather than the deplorable state of education for the working classes and the poor. Why is this?

First, we have bought into this official messaging that “change takes time”. Of course, it does, but it is now almost 30 years into democracy, and something as powerfully symbolic and practically soluble as pit latrine toilets are still in place.

Also, a policy measure of the “change takes time” argument is to demonstrate progress against time. You would be hard-pressed to accept that even one-third of underserved schools are now better off in terms of physical infrastructure or mathematics and science outcomes than in 1994.

Second, we seem to have accepted the trials and conditions of education in black schools as “normal”, but not so in the former white schools.

I have marvelled, for instance, at the quiescence in underserved communities when it comes to education deprivations, however, when there is a reported case of racism in a former white school, such as happened when black girls were required to wear their hair according to white standards, then the nation goes berserk. But when a teacher molests a child or a principal is shot on the grounds of a township school, there’s barely a reaction.

Third, and related to the previous point, the goal of most black parents is to escape those conditions of schooling, not reform them. That is why there is an annual stampede among parents from disadvantaged communities to get into those schools.

Those African parents with less money aim for the former Indian and coloured schools as they are perceived to offer marginally better education than in the townships. All parents who are not white, but with more money, push to get their children into the former white public schools, while newly wealthy black families can afford to pay the ridiculously high fees of the upper-tier private schools.

Township schools are literally abandoned by desperate parents.

It makes sense, of course. When your child is in a dysfunctional school you cannot wait for this government to make real differences in the operational status and academic outcomes of the poorest institutions. And then there is the harsh realisation that this government is not going to make any radical changes to the school system for the foreseeable future.

That is why in places like the northern areas of Gqeberha you have this dramatic shift from the African township schools to the former coloured schools on the other side of a freeway, simply because of opportunities perceived to be marginally better. It is what any reasonable, decent parent would do.

That is the tragedy of the moment: that black citizens have given up on their government as the source of educational renewal, let alone social justice, in the public school system. It is not going to happen, and in the meantime, children desperately need access to a quality education.

After all, the most powerful evidence of appropriate action is where public officials send their own children. It is certainly not township schools or ones in which their children are taught by black teachers as powerful role models or learn in indigenous languages.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.