SA Mining

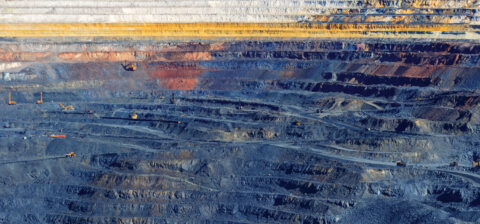

Will The EU’s CSRD Put More Pressure On The Mining Industry?

Dr Andries van der Linde, PhD, Head of Renewable Energy at SSC Group

The term “from cradle to grave” has never been more applicable and had more of an impact on how business is conducted than it currently does in the mining sector. So much so, in fact, that in some cases it can become a company’s death knell if not taken into consideration, especially if a South African business entity wants to export to Europe.

The European Commission announced the adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which will take effect in 2026. It may sound and seem like it is something completely new, but it is merely more of the same with a new cloak.

The CSRD’s objective is to establish a consistent and congruent environmental, social and governance (ESG) implementation and execution. Reporting requires extensive and detailed disclosures about how sustainability issues affect a company’s business, as well as the impact of its activities on society and the environment.

Reporting on sustainability is becoming increasingly important for investors and stakeholders, their decision making and assessments on how value is created for the company, and for society. This is applicable to more than 50 000 businesses operating in the European Union (EU), regardless of where they’re based, and it affects all those who do business with Europe equally. Such reporting requires all-encompassing disclosures on how sustainability matters affect a company’s business, as well as the effect of its activities from an ESG perspective.

The immediate reaction would be that this is Europe and not South Africa. However, coupled to this is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which will place a carbon price/tax on some of the most emissions-intensive industrial goods imported into Europe.

CBAM reports

This adds an additional emphasis on the “E” in ESG, with the climate change component coming to the fore. The application will be in the form of a price adjustment via purchasing certificates – where one CBAM certificate equates to one tonne CO2 equivalent. This means that although the apparent reference is only to carbon, it applies to the full spectrum of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG).

Therefore, importers will need to submit a CBAM report to the European Commission, declaring the total GHG embedded in a consignment, including emissions released during mining and manufacturing (direct emissions), certain upstream emissions and indirect emissions such as transport.

How does it affect South Africa and the local mining industry? From July 2024, using default values rather than primary data will result in fines. SA faces significant vulnerability due to CBAM. In the short term, approximately R52.4-billion of South African exports are at risk, with energy-intensive products specifically targeted. Steel is likely to be the most affected.

The only way to mitigate this is to implement GHG mitigation measures. Although mines are expected to implement such measures, it is not that simple, because at the end of the day it is all about cash flow. And although it will have a direct impact on products landed in the EU, the ripple effects will be felt throughout the value chain. If SA products become uncompetitive because of the additional cost resulting from CBAM, the mining industry will be equally affected.

When considering steel as a prime example, its carbon footprint follows it every step of the way. Calculating a product’s carbon footprint can be extremely complex and the variables can be endless, depending only on the attention to detail and accuracy.

When it comes to mining, the carbon footprint mainly comes from energy; and in this regard, electricity and diesel are the main contributors.

In 2023, the Minerals Council South Africa’s estimates on carbon tax paid by the mining sector were between R3.7bn and R4.6bn, and are expected to be R4.34bn to R11.65bn by 2030. Then there is carbon tax every step of the way until the final product. These are already not insignificant amounts, and now the CBAM will be added to the final product.

In South Africa, the steel industry exhibits two main processes to produce steel. Depending on the source, approximately 60%-80% of the steel is manufactured using the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace process, where steel is produced using iron ore and coking coal as raw materials.

The balance is produced by employing electric arc furnaces, where scrap steel is the main component, and the Corex process, where normal coal is used together with iron ore. As a result of the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace route – raw materials being iron ore and coking coal – its carbon footprint is 1.987 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel produced. This as opposed to 0.357 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel with the electric arc furnace route, where recycled steel makes up most of the input. Meanwhile, the Corex process’s carbon footprint is 1.2 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel produced.

The coal conundrum

As for the biggest contributor to steel products’ carbon footprint, it should be remembered that most of the coking coal used in SA is imported from Australia, the US and Canada, which dominate metallurgical coal markets.

However, once developed, the Makhado mine in Limpopo will be the only significant hard coking coal mine in the country, and is poised to play a prominent role in the steel manufacturing industry.

However, back to the CSRD. The only solution is to reduce the carbon footprint of products exported to Europe. For steel, the following options are available:

- The industry must reduce its dependence on Eskom and reduce energy consumption and/or move to renewable energy sources.

- Move from diesel vehicles to electric vehicles, green hydrogen- or renewable energy-charged batteries. Implement green steel processes.

However, this is a double-edged sword, because this will have a direct impact on the coke coal mine in Limpopo, as well as mines that supply normal coal to smelters employing the Corex process. Unfortunately, with emissions targets of 45% by 2030 and net zero by 2050, the pressure is on and to achieve those goals.

In the end, the main losers in achieving these targets would be the producers of fossil fuels. However, there are still those who are fossil fuel-dependent, whether manufacturer or miner, and for these players, adaptation will be critical to survive.

Ultimately, it will take a concerted effort from all industries in the value chain, which will have to work together if they hope to remain in line with the CSRD legislation.