SA Mining

The Dark Side Of Cobalt Mining

Renewable energy from solar and wind sources is essential for the decarbonised domestic and global economy. Rechargeable batteries containing the mineral cobalt are used to store electricity produced by these and other renewable energy sources. These batteries are critical for the continued electricity supply when the wind is not blowing, the sun is not shining, and the tides are not flowing.

Cobalt is quickly becoming an in-demand mineral critical to the green energy supply chain and is a part of the base metal group that is becoming the heart of the renewable energy transition. It is a critical component of battery materials that power electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable energy sources and is facing a sustained surge in demand as decarbonisation efforts progress.

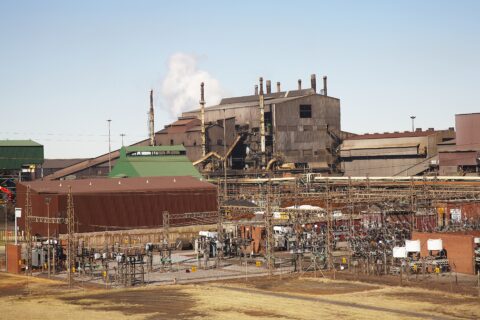

Due to the push for global decarbonisation, countries have begun to renew minerals exploration, with African countries such as South Africa relying on secondary exploration to maintain existing operations. South Africa is one of many African countries with a cobalt supply, with the Kruisrivier mine currently being worked commercially, with operations focused solely on cobalt.

Speaking to Tebogo Kale, director of Gravitas Minerals, about the increased occurrence of secondary mining opportunities in South Africa concerning cobalt and other battery materials, he says: “We are currently seeing strong demand for base metals such as cobalt, manganese, and zinc within South Africa. The main province of interest is the Northern Cape, which will become the new renewable minerals mining Mecca.”

Cobalt and the green energy transition

The uses of cobalt are as diverse as they are enduring. First isolated as a metal in 1739, cobalt has formed the cornerstone of many essential applications in operation today, from alloys used in jet turbines, hard metals and orthopaedic implants, to clean fuels, and the inks and pigments applied to pottery, enamel and glass.

It is also the active constituent of vitamin B12 and is essential for human and animal health and vitality. But the most significant use of cobalt, as the world develops more sustainable energy solutions, is as a raw material in rechargeable batteries.

“More than 50% of the cobalt produced globally today is found in rechargeable batteries, namely those used in portable devices, stationary applications, and e-mobility,” says Shane Bradshaw from Energy Management SA.

“As electric modes of transportation continue to evolve, the demand for battery commodities like lithium-ion and cobalt is set to increase, amid concerns over whether there are sufficient amounts available,” he says.

The Cobalt Institute (CI) is a non-profit trade organisation that promotes the responsible and sustainable production and use of cobalt in all forms. CI past president David Weight explains about the growing importance of cobalt in the renewable energy market and why this metal – and others – will play an essential role in the green energy transition.

How is cobalt currently sourced?

“It is important to realise that over 90% of cobalt is produced as a by-product of large-scale copper and nickel mining. The only small exception to this is Managem’s Bou-Azzer mine in Morocco, which mines cobalt as a principal metal from a polymetallic sulphide ore,” says Weight.

“The majority of cobalt (70%) comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) as a by-product of large-scale copper mining and there is a proportion produced through artisanal and small-scale mining operations too. This activity is perfectly legal and often at subsistence level, but is very poorly regulated.”

All in all, he says, the large-scale mines, particularly those in the western jurisdictions, “operate to standards of international best practice and have very well-established Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (ECG) programmes”.

“As such, these mines will have environmental stewardship, occupational health and safety etc., and will be highly regulated. Over the past 30 or 40 years, there has been a much bigger push for sustainable mining practices, and you will see from the larger mining companies that within their ECG obligations, there are sustainable performance requirements that must be adhered to.”

International metrics will also measure the sustainable performance of the more significant copper and nickel producers, and they are expected to validate their performance independently and transparently, too. The most critical concern for cobalt and all metals and minerals is that they are responsibly and sustainably sourced and used.

Responsible sourcing means that when you source your raw material, you know who has provided it and that it is being produced in an ethically acceptable way. Issues around sustainability are constantly addressed and improved because globally, the environmental footprint of any product must be measured to assess its environmental impact through its life cycle.

How vital is cobalt in the renewable energy market?

“At the moment, it is bordering on the essential,” says Weight. “We must look at this in a broad context because, in the first instance, a paradigm shift occurs from the internal combustion engine to electric mobility, driven by the global desire to decarbonise global economies.”

For example, he notes that the massive change from the horse-drawn carriage to an internal combustion engine is similar to the shift from the internal combustion engine to the rechargeable batteries used for electric mobility. It will be a substantial disruptive transition.

“The world will wean itself off fossil fuels and look more towards renewable energy. This is only possible with a specific suite of energy metals and rare earth elements.

“The lithium-ion battery has changed the game enormously, permitting electric mobility, and most lithium-ion batteries contain cobalt, including lithium-nickel-manganese-cobalt-oxide (NMC) and lithium-nickel-cobalt-aluminium-oxide (NCA) batteries.

“The batteries with the highest specific power density and specific power capacity contain cobalt. Without access to this whole suite of metals, there will be no energy transition.”

Artisanal mining – why it’s vital for the renewable energy transition

In 2020, South Africa produced 1 800 metric tonnes of cobalt, which is only a fraction of the total annual global cobalt mine production of roughly 140 000 metric tonnes. Staying in Africa, cobalt is currently being mined in the DRC, Madagascar, Morocco, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe has one of the world’s largest copper and cobalt reserves. The world’s largest cobalt supplier is, however, the DRC, where it is currently estimated that up to a fifth of cobalt production in the country is produced through artisanal miners.

The DRC accounted for more than 70% of the world’s cobalt production in 2019, producing 100 000 metric tonnes. As a result, many of the world’s largest mining companies have established operations within the DRC.

The Katanga Province is a productive region within the DRC, home to some of the world’s biggest cobalt mines, including Mutanda, Kamoto, Etoile and Ruashi.

However, a significant artisanal mining sector has also bloomed in recent years, buoyed by growing demand for cobalt. A report from the World Economic Forum (WEC) estimates small-scale mining accounts for 15%-30% of all cobalt production in the DRC.

For years, human rights groups have documented severe human rights issues in the DRC’s artisanal and small-scale mining. The DRC is a country where violent ethnic conflict and high levels of corruption have weakened oversight. Child labour, fatal accidents and violent clashes between artisanal miners and security personnel of large mining firms are recurrent within the DRC’s cobalt mining landscape.

Efforts to meet the demand exerted by EVs have been focused on increasing the cobalt supply. In 2021, the DRC was estimated to be producing between 60% and 70% of the world’s cobalt supply.

Most of the extracted cobalt is a by-product of existing copper mines. However they cannot increase their output to meet existing demands and have little financial incentive until copper prices also rise to complement mining activity. The other primary source of cobalt outside existing copper mines in the DRC is produced via artisanal mining, which is estimated to produce up to 15% of the global cobalt supply.

Given that artisanal miners within the DRC are producing more than Russia – the world’s second-largest producer – their role and the conditions under which they operate are essential to understand. Artisanal miners hand-dig higher grade ores than those extracted through industrial or mechanised production. But there are well-reported problems with artisanal mining regarding social and environmental costs.

The small mines in which artisanal miners operate are often dangerous and polluting. The mining and refining processes are often labour-intensive and associated with various health problems due to accidents, overexertion, exposure to toxic chemicals and gases, and violence. And these miners, known locally as creseurs, are so economically reliant on this informal economy that these dangerous conditions cannot afford full consideration.

The environmental costs of cobalt mining activities are also substantial. Southern regions of the DRC are home to cobalt and copper and large amounts of uranium. In mining regions, scientists have made a note of high radioactivity levels. In addition, mineral mining, like other industrial mining efforts, often produces pollution that leaches into neighbouring rivers and water sources. Dust from pulverised rock is also known to cause breathing problems in local communities.

International firms that trade, refine and supply cobalt have been trying to understand how cobalt from artisanal mining has entered their supply chains. While in theory there are legal differences between industrial and artisanal mining supplies, the boundary between the two remains quite blurry. Although there have been pledges from companies to increase transparency regarding their cobalt sources and refineries, or promises to buy exclusively from other countries, very little in the conditions in the DRC has changed.

One reason there’s been so little change in the region in a decade is the strong economic incentives from artisanal mines. It is currently estimated that between 140 000 and 200 000 people work as artisanal miners in the DRC and most earn less than R170 per day.

Considering the vast economic incentives, both domestically and internationally, to keep artisanal cobalt mines open, what does the green energy transition look like next?

Can cobalt mining be improved?

Given that cobalt-based batteries are a crucial and inevitable part of the green energy transition, large-scale industrial and artisanal mining are here to stay. A WEF white paper in 2020 outlined the current state of artisanal cobalt mining in the DRC and offered recommendations to make the industry fair and safer.

Among them is the formalisation of a traditionally informal economy, which would include adopting common standards and metrics, establishing a monitoring and assessment process, and knowledge-sharing to ensure that a formalisation process is a multi-stakeholder one.

The Global Battery Alliance (GBA), a multi-stakeholder organisation to establish a sustainable battery value chain, recently launched its Human Rights Index and Child Labour Index for the Battery Passport, ahead of Human Rights Day on 10 December 2022.

The indices are the world’s first frameworks to measure and score the efforts of any company or product specific to the battery value chain, towards supporting the elimination of child labour and respecting human rights.

Benedikt Sobotka, co-chair of the GBA and CEO of Eurasian Resources Group, says: “It is crucial that the rapidly rising demand for batteries does not come at the expense of adults’ or children’s basic human rights.

“The GBA is proud to have launched these human rights and child labour Indices, which aim to immediately and urgently eliminate child and forced labour, strengthen communities and respect the human rights of those employed by the battery value chain. The rollout of these indices has been possible thanks to the GBA’s global, collaborative approach, and we look forward to developing them further with valuable input from our members.”

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.