Business Day 25 Years of Democracy

Wasted! A Descent Into Corruption

On a Sunday morning in April, I was in Phelandaba outside Mangaung. The book Gangster State by Pieter Louis Myburgh had just dropped and it detailed how much had been wasted to corruption in the Free State under the administration of provincial strongman and former premier, Ace Magashule.

In Ward 13, I found a group of residents in ANC T-shirts, caps, or under ANC umbrellas. In other words, they were loyal members. Along the streets, the majority of posters strung up were ANC — featuring a beaming President Cyril Ramaphosa. Occasionally, I saw an EFF poster featuring its president Julius Malema. In other words, there is only one big story in this part of town.

I asked residents about this loyalty and, in answer, they pointed to a school, a playground and RDP houses as evidence of the ANC’s social delivery to them. But Myburgh’s book painted a picture of such corruption that you just know there was more available and that the area could have so much more by way of public goods.

Billions lost

By most accounts, and in my research, South Africa has conservatively lost R100-billion to state capture or to corruption only in the past 10 years. If you extrapolate this into houses, electrification, access to water and other public goods the sense of waste becomes clearer.

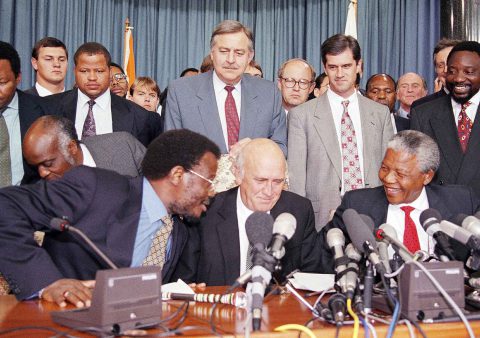

When it won a mandate for liberation in 1994, the ANC did not inherit a clean slate. The apartheid state was a corrupt polity and the new government did not sufficiently and quickly enough change the culture it inherited, either through how it procured in the public sector through to the benefits the Ministerial Handbook provided to public servants.

Very early on, the new party was hit by scandal. In 1996, the first one struck. The Department of Health sought to fund an AIDS education play based on the success of Sarafina, the musical. It entered into an extravagant contract with playwright Mbongeni Ngema who never delivered, and once in the public domain, the scandal quickly went viral and was considered a fall from grace for all involved.

Tender scandal

Then, in 1997, the first big tender scandal became national when then housing minister Sankie Mthembi-Mahanyele arranged a contract for her friend in the Motheo housing scandal. Her director-general, Billy Cobbett, warned against the contract and he lost his job.

The Auditor-General made an adverse finding, but the ANC government swatted it away laying the foundation for two trends that continue to haunt South Africa today: it is now a trend for politicians to move portfolios with their own pliable bureaucrats, and Auditor-General reports are items only of a historical account. In very few cases, is an adverse Auditor-General’s report acted upon.

Arguably, because these first dalliances with a corruption of systems and procedures were ignored in the governing party, the first big dance with the devil was allowed in 1999.

Still under Nelson Mandela’s government, the ANC ignored internal dissent, in 1999, to sign the Strategic Defence Package or what we now call the arms deal. The new government had inherited a scorched earth and a near empty fiscus, but it pushed ahead with an extravagant purchase of arms soon after it secured a peace heralded around the world.

It is now legend how the arms merchants from Germany and France secured political support at various levels of the state, notoriously through the well-connected Shabir Shaik who was the personal financial adviser to then KwaZulu-Natal MEC, Jacob Zuma.

Arms deal

The arms deal has haunted South Africa for a full 20 years now and in May this year, Zuma will be in the Constitutional Court to fight off allegations related to his personal enrichment. The arms deal marked the beginning of the end for the ANC’s ability to fight corruption.

Instead of dealing with the corruption, then president Thabo Mbeki set a precedent when he allowed ANC dissenters to be marginalised and pushed out of the party. Institutions including Parliament, the Auditor-General, the Special Investigating Unit and the Public Protector all dissembled in the face of political pressure and set the stage for much worse to come.

In 2005, the Oilgate scandal in which ANC loyalist Sandile Majali won a Petro-SA contract for R15-million and immediately discharged R11-million to the ANC notched up a new precedent. With the Public Protector’s failure to investigate properly, the pattern of turning a blind eye to cronyism laid the ground for full-on state capture.

Majali (who passed away before he could face the law) was an early exemplar of a trend we now know too intimately: the patron who feeds profits back into the party.

Bosasa in the news

In 2006, Adriaan Basson alerted the public to the first stories of Bosasa, the facilities management company owned by the Watson family of Port Elizabeth. Bosasa was winning contracts by bribing Correctional Services officials, Basson’s first reports show. The Watsons were also ANC loyalists who parlayed their political history into a post-apartheid fortune.

Before the Zondo commission of inquiry into state capture, the company’s former COO, Angelo Agrizzi, had laid out the sordid detail of how the company was run as a front for the ANC. Another ANC front company, Chancellor House, gave itself huge contracts in the build of the new power stations, Medupi and Kusile, through partnering with Hitachi.

The timeline of corruption (drawn up on page 30) leaves out many smaller scandals -— but after Bosasa and Chancellor House, a new and more dangerous scandal pattern emerges. In 2007, the country’s first black police commissioner, ANC luminary Jackie Selebi, was charged with corruption. The underworld mastermind, Glenn Agliotti, made a plea bargain with the National Prosecuting Authority in which he revealed how he had paid cash bribes to Selebi over years.

In 2010, Selebi was convicted of bribery. This story has been replicated again and again with different characters as the underworld has infiltrated both party and state.

Gupta family patronage

From this point on, scandal became the rule rather than the exception as the ANC battled the demon: by 2009, journalist Mandy Rossouw uncovered the beginning of the story of Nkandla, the state-sponsored enrichment of then president Jacob Zuma’s personal estate in northern KwaZulu-Natal.

Ten years later, there has been no accounting for that enrichment. One year later, a new crony network was blown into the open as amaBhungane, the investigative journalism hub, broke the first story of how a family from India, called the Guptas, had come to quickly exercise influence over Zuma, who had been in office for only a year by then.

The Gupta family patronage network so secured influence over key sectors of the economy that their activities gifted a new term into the South African lexicon: state capture. Four commissions of inquiry were constituted between 2018 and the first quarter of 2019 to probe various aspects of state capture as South Africa began a concerted effort to deal with corruption. What started as a play became a full-on drama 23 years later. The jury is out on how successful this fight will be.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.

Sign-up and receive the Business Media MAGS newsletter OR SA Mining newsletter straight to your inbox.