SA Mining

Striking The Balance

By Rodney Weidemann

As Africa enters a critical decade of energy development and industrialisation, the demand for reliable power, sustainable infrastructure and clean energy sources is reshaping the investment landscape. At the same time, the imperative to transition responsibly – without infringing on the rights of individuals or communities – is more urgent than ever.

According to Pooja Dela and Dylan Cron, partners at Webber Wentzel, business and human rights (BHR) offers a framework for managing this tension.

“Rooted in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), it sets out how businesses should respect human rights throughout their operations and supply chains, and how states must protect those rights through regulation, enforcement and access to remedy,” notes Dela.

“For energy stakeholders such as governments, investors, developers and communities,” continues Cron, “BHR is no longer a peripheral concern. It is a core driver of responsible growth, risk management and legitimacy in a rapidly evolving global and African energy ecosystem.”

People-centred transition

Luca Maraschin, senior associate at NSDV Law, adds that he is of the view that the energy transition should be people-centred. Simply being “green” is not enough – new projects must not perpetuate the status quo and the historical inequalities that large projects may have caused.

“To ensure BHR principles are embedded in energy development, companies must strive to conduct thorough human rights due diligence throughout the lifecycle of energy projects, involve affected communities early and continuously in decision-making, and ensure collaboration with affected communities in renewable energy projects,” he says.

“Part of this is to go ‘beyond compliance’, by going further than what is required by the local jurisdiction’s regulations, and to truly embed communities into all considerations relating to such projects.”

Embedding BHR into the energy transition is not just ethical; it is strategic, he claims. In NSDV’s experience, companies that proactively manage human rights risks build a social licence to operate, reduce project delays caused by legal challenges and conflict, and attract responsible investment.

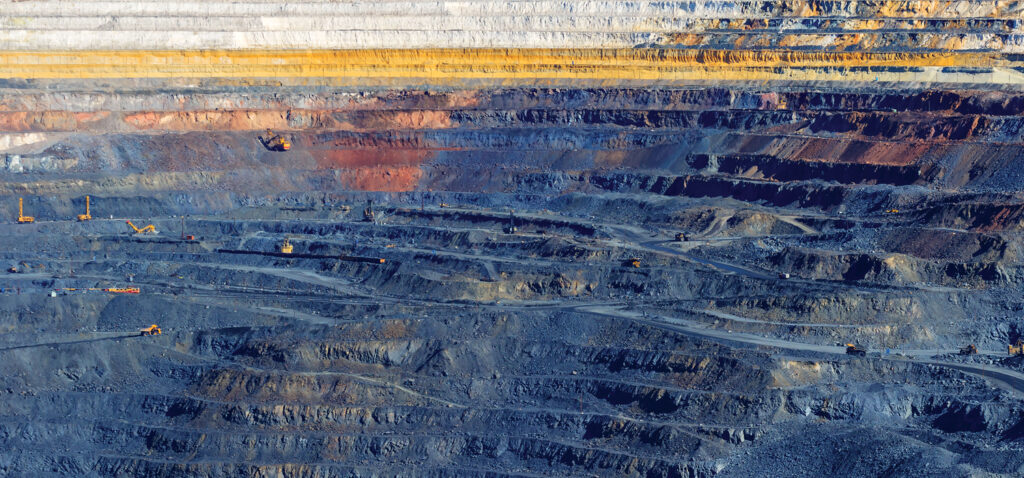

“In Africa’s dynamic energy ecosystem – where rapid growth meets systemic inequities – respecting rights is foundational to legitimacy, both locally and globally. By way of example, numerous large-scale projects in the mining and oil and gas sectors have been halted, due to inadequate public participation and the exclusion of impacted communities in the regulatory processes,” says Maraschin.

As such, minimising this risk is not only a question of ethics, but also good business, he says.

There are two phases implementing an effective energy solution, says Wickus Botha, energy and resources industry lead at EY. The first is the construction phase, and the second is the operational phase.

“It certainly makes sense in both phases to hire people who live close by, in the surrounding communities. It brings them closer to the asset, it improves their skills, reduces cost and transport challenges, and, ultimately, the money earned by these employees will be spent in their local communities,” he says.

“Furthermore, in the initial phase, a mine won’t get permission to go ahead with any construction without the approval of relevant government agencies, and such approvals require an environmental impact assessment (EIA) and plan. A properly conducted EIA will, of course, take into consideration the environmental impacts on the surrounding communities.

“What this means is that a lot of protections are already built into existing legislation, as well as individual company processes. Therefore, as long as these operations follow the legal processes, BHR should be taken care of,” says Botha.

Challenges and risks

Nonetheless, there remain risks for organisations that fail to effectively implement BHR practices, according to Simon van Wyk, Africa sustainability leader for strategy and transactions at Deloitte.

He points out that risks to human rights come in many different shapes. For example, there is a potential risk to community livelihoods, so it is imperative to understand how your project may impact the existing ways in which the surrounding community makes its living.

“Another risk is the displacement of people, particularly with energy projects that require a large footprint – this could lead to a potential resettlement of the community, impacting their ancestral land, and thus their culture and heritage,” he says.

“Large projects are also often magnets for attracting people from around the country. A large influx of new people into an area often leads to an increase in crime rates, with the concomitant impact this has on vulnerable women and children’s rights to safety and life.”

Speaking of the risks those companies that fail to implement BHR may face, Van Wyk indicates that a core risk is that of reputational damage – something that is increasingly impacting on businesses and which should thus be taken very seriously.

“Another challenge hindering the implementation of BHR is that the policing of regulations, and the punitive measures that follow, are different in every country. In SA, for example, we have the National Environmental Management Act (NEMA), which has relevant punishments built into it. However, this is often not proportionate to the impact of the project – the fines levied are often less costly than following the law. Thus, unscrupulous players may consider it a cheaper option to simply commit the crime and pay the fine.

“A final risk is that failure to adopt BHR as standard practice could lead to your company not being allowed to sell its products in certain markets where BHR forms part of their many rules and requirements for conducting global trade,” he adds.

Comprehensive frameworks

Chantal van der Watt, PwC South Africa director for sustainability, explains that energy developments can achieve both cultural protection and environmental sustainability, through implementing comprehensive frameworks that recognise host communities as a key stakeholder – while establishing robust environmental safeguards throughout project lifecycles.

“Environmental degradation prevention must address cumulative impacts. Water quality and ecosystem health remain paramount concerns, reflecting the holistic environmental approach characteristic of indigenous land management,” she says.

Ongoing stakeholder engagement is equally vital, rather than once-off processes. Human rights impact assessments recognise that human rights conditions evolve and companies need to consult with affected stakeholders throughout the project cycle, to renew community consent regularly.

“The key principle is that energy developments must be designed from the outset to enhance, rather than undermine, host community cultural rights and environmental protection. One needs to recognise that these two objectives are fundamentally interconnected and mutually reinforcing when properly implemented,” says Van der Watt.

It should be mentioned that companies that fail to integrate BHR run the risk of reputational damage, notes Trevana Moodley, an associate at NSDV Law. From activism, to media exposure, and on to community opposition, all of these actions can discourage investment and lead to divestment by ESG-conscious investors and financiers. In short, BHR non-compliance is increasingly a business risk, not just a moral failing.

“In Africa, land tenure systems are often informal, governance structures may be weak, and many communities have suffered historic marginalisation. Integrating BHR into local energy projects helps to recognise and protect customary land rights, involve marginalised voices in decision-making, build resilience in governance through inclusive policies, and foster trust between developers and communities.”

Ultimately, the integration of BHR into the energy transition unlocks sustainable growth, she says. “It aligns business strategy with societal values, mitigates systemic risks, and promotes inclusive development. In a world where energy is a cornerstone of prosperity, ensuring it is developed responsibly is not only the right thing to do – it is the smart thing to do.”